Материал раздела Основной

Личность лидера определяет финансовый успех компании. Поэтому она обречена на провал, если ее руководитель больше думает о личных мотивах, забывая о бизнес-целях. Директор по сбыту Siemens Татьяна Дроздова рассказывает, как это происходит

Сегодня неопределенность и неуверенность в завтрашнем дне поставила новые задачи перед руководителями. Им приходится искать в себе ресурс для решения нестандартных проблем в бизнесе, быть гибкими и чаще анализировать свое поведение — а также отклик на него со стороны подчиненных. Особенности личности лидера могут привести компанию как к успеху, так и к краху.

Деструктивные паттерны руководства

Посмотрим на несколько дисфункциональных моделей поведения СЕО, которые превращают компанию в деструктивную.

- Микроменеджмент — стремление к чрезмерному контролю и совершенству подчиненных, что приводит к повышению общего уровня недоверия в компании.

- Стремление избегать конфликтов — когда отсутствие разногласий важнее соблюдения границ руководителя. В этом случае лидер характеризуется как слишком мягкий и, по сути, не является руководителем.

- Третирование подчиненных — характерно для руководителей с потребностью во власти и повиновении. Доводят компанию до высокого уровня агрессии внутри коллектива.

- Маниакальное поведение — практикуют люди, склонные к тем или иным формам одержимости. Например, она может быть направлена на наведение порядка в компании в ущерб клиентскому сервису.

- Недоступность. Пример — руководители, которые взаимодействуют с коллективом через своих помощников. Результат — неведение сотрудников и непонимание реальной ситуации внутри фирмы.

- Интриги как способ фиксации власти. Например, руководитель дает одинаковые задания различным подчиненным с целью создания конфликта между ними. Результат — компания занята внутриусобными войнами вместо фокуса на продажах.

Как управленцу понять, что некоторые его личные качества негативно влияют на доверие подчиненных, их инициативность и атмосферу в коллективе. И как исправить эти недостатки?

Принято считать, что эффективный руководитель отличается развитыми компетенциями. Это так лишь отчасти и вот почему. Представьте себе управленца, который обучен, компетентен, опытен. Он прошел должное количество тренингов, а жизненные ситуации научили остальному. Руководитель потратил много времени на сплочение команды, вовлечение ее в цели, верит в свое детище.

И вот готовит ежегодную стратегическую сессию для утверждения планов на будущий год и на этой сессии не выдерживает и орет на одного из топ-менеджеров, пришедшего недостаточно подготовленным. Как результат – люди демотивированы, топ готов писать заявление, инициатива команды «на нуле», доверие – там же. Атмосфера в команде разрушена.

Что такое деструктор?

Деструктор переводится как «разрушитель». Это конкретные негативные проявления характера руководителя, способные привнести разрушения в его дело, в его планы, в самооценку, здоровье, в отношения с другими людьми, с командой, в энергию цели, в стратегию, в прибыль компании и так далее. Предположительно, деструкторы есть у каждого из нас, вопрос в их степени и влиянии на нас, наше дело, а также на отношения с окружающими.

Какие виды деструкторов руководителя бывают?

Это плохое настроение, излишняя эмоциональность, неуважительное отношение, крик… Если их систематизировать, мы получим следующие виды деструкторов:

1. Деструкторы давления: излишняя агрессивность, грубость, высокомерие, несдержанность в проявлении негативных эмоций по отношению к другим. Подчиненные, которые сталкивались с подобными «давящими» проявлениями руководителя, чаще всего говорят, что падает мотивация, вовлеченность, желание работать и проявлять инициативу. Портится настроение, у многих начинаются эмоциональные проблемы, ведущие, в том числе, к выгоранию. И конечно, падает эффективность и продуктивность в команде.

2. Деструкторы избегания: руководитель проявляет излишнюю осмотрительность, нерешительность, неготовность принимать решения, «ставить точку», избегает любых, даже разумных рисков, потерь и недовольства других людей, связанных с принимаемым решением. Последствия этого деструктора – упущенные возможности, тающая сила лидерского статуса и вера в лидера, демотивация команды из-за нерешительности. И как следствие – общее снижение результативности.

3. Деструкторы нестабильности: когда руководитель демонстрирует эмоциональную неустойчивость – неспособность выносить давление и стресс, излишнюю чувствительность, склонность все принимать близко к сердцу. С таким руководителем сложно вести диалог, рассматривать проблемы, критику – слишком большой риск получить чрезмерные эмоции. Как следствие – проблемы замалчиваются, не решаются, инициативы не обсуждаются.

Ключевые проблемы руководителя при работе с деструкторами

Наверняка вы замечали те или иные виды деструкторов у других людей или даже у себя. Причем разные деструкторы могут проявляться у разных людей в разных обстоятельствах, или не проявляться. Например, на работе руководитель склонен проявлять агрессивность, а дома – нет. Даже осознавая негативные последствия деструкторов, у руководителя могут быть две проблемы:

1. Действие деструктора проще заметить у других, чем у себя. Некоторые деструкторы так хорошо «маскируются» под «сильные» стороны или качества личности, что долгое время остаются незамеченными для самого человека.

2. Даже зная о наличии своего деструктора, им крайне сложно управлять в моменте. Чаще мы лишь постфактум осознаем, что сработал деструктор и нам остается лишь сожалеть или ругать себя. А в моменте – он сильнее нас, на то он и деструктор!

7 популярных форм проявлений деструкторов руководителей

Чтобы деструкторы были нами замечены, важно знать их «в лицо», понимать – какие есть характеристики, маркеры, признаки деструктора. И развивать осознанность, чтобы отслеживать собственные проявления.

1. Упертость, жесткость

Пожалуй, самым популярным, сложным и важным деструктором является то, что принято называть упертостью. Когда-то это качество помогло руководителю стать тем, кем он является, и сейчас помогает добиваться своего. Но оно же стало его деструктором. Благодаря упертости он стал слишком жестким, думает, что всегда прав, что точно знает – что и как нужно делать.

Он перестает слушать и слышать других, занимает авторитарную позицию, перестает воспринимать критику, давит на сотрудников, партнеров и близких, он даже считает, что ухватил жизнь за хвост и управляет ей. Команда такого руководителя демотивирована, сильные сотрудники не задерживаются, инициатива в такой команде не приветствуется, а сам руководитель «страдает» из-за нерадивых подчиненных, сохраняя большую часть управления в ручном режиме.

2. Перфекционизм

Такой руководитель стремится сделать все хорошо, безошибочно, правильно, просто идеально. Ошибки недопустимы, за каждый промах следует наказывать и себя и сотрудников. К ошибкам управленец относится как к проявлению собственного несовершенства, недостаткам. Ему стыдно допускать ошибки и признавать их. Он болезненно реагирует на критику. Он не склонен рисковать, постоянно критикует других и их инициативы, чем убивается мотивация и желание предлагать что-либо.

Такой менеджер существенно отстает в профессиональном развитии от тех, кто действует смелее. Ибо ошибки учат других, а его – нет.

3. Обесценивание

Менеджер не дает шанса сам себе, как бы говоря – «да куда мне». Он снизит цену, побоится назвать больше, побоится отказать, даже когда не хочет делать то, что его просят. Он стремится быть услужливым, старается помогать, когда самому неудобно, склонен жертвовать собственными интересами в угоду другим. Его легко продавить, добиться от него уступок.

Он может находиться в позиции жертвы, убежденный, что не заслуживает большего, хорошо, что имеет то, что имеет. Он также склонен превозносить других, как и обесценивать тех, кто ему близок. Сотрудникам такого руководителя надо быть готовыми к тому, что их идея или инициатива будет встречена холодным «займитесь своим делом» или «да куда ты лезешь!».

4. Самобичевание

Такой менеджер винит себя, ругает себя за ошибки, за недостатки, за события в своей и чужой жизни, за проблемы в бизнесе, с сотрудниками и клиентами. Если что-то идет не так, то он «сам виноват». Он не может себе простить прошлого, потерь и неуспеха. Его сопровождает чувство вины.

Такие люди склонны жаловаться, обвинять внешние обстоятельства, искать виноватых в проблемах, наказывать, переходить на личности. Демотивируя и себя и других таким поведением, они успокаиваются только тогда, когда нашелся виновный.

5. Безразличие

Такому менеджеру нет дела до себя. Главное в его жизни – это бизнес, дело, работа, семья, дети, клиенты и так далее. А сам и свои интересы – подождут! Здоровье? Тоже подождет! Нужно сначала так много успеть, он так много должен сделать для мира, для родных, для компании и клиентов, что на себя просто нет времени.

В равной степени он может поручить вам задание, а потом «забыть» про вас, не давать обратной связи и вообще, управлять издалека. Тем самым демотивируя команду, не понимающую, насколько важно и ценно то, что она делает для компании и лично босса. Жертвуя своими интересами, своим здоровьем «ради вас», он рано или поздно предъявит вам счет. Как?! Вы не оценили его жертвы?! Тогда получай, неблагодарный!

6. Отсутствие уважения

Такой человек, прежде всего, не уважает себя. Свои границы, свое слово, свои ценности и особенности, свои обязательства. Он позволяет другим нарушать его же границы, проявлять неуважение к нему и его главное свойство – умение терпеть и прощать. Как ему кажется – это хорошие качества. Но кто будет уважать его, если он не уважает себя сам?

Другие, считывая отсутствие самоуважения, проверяют личные границы человека. Чувствуя их отсутствие, они, например, нагружают такого коллегу заданиями, работой. А тот берет все больше и больше, безропотно соглашаясь. Грузят того, кто везет! Стерпев хамство в свой адрес единожды, он начинает получать его регулярно. В отношениях с другими позволяет себе наорать, нахамить, оскорбить, нарушить собственное обещание, проявлять неуважение к личным границам, личностным, гендерным, возрастным особенностям другого.

7. Жалость к себе

Намереваясь начать новую жизнь с понедельника, и открыв глаза утром, такой человек думает, что пока не готов, ибо… Дальше по списку, начиная с плохой погоды, такого же настроения и вообще слишком сложного пути. Он ленится выбираться из привычного комфорта, начинает что-то и бросает, столкнувшись с трудностями. А в отношениях с другими это тот самый человек, которого хочется спасти, «причинить» ему добро, пожалеть, дать ему еще шанс.

Он тот самый человек, которому снизят нагрузку, которого не уволят даже за косяки, потому что «человек хороший». Он и сам склонен жалеть других и давать послабления, помогать там, где не просят, вмешиваться в чужую жизнь, а непрошеный совет – его визитная карточка.

Откуда берутся деструкторы?

Как следует из исследования Школы бизнеса Дардена 1986 года «Почему люди ведут себя именно так», в основе наших действий, а также восприятия действий других, лежат так называемые фильтры восприятия. К фильтрам относятся: пол, возраст, убеждения и верования, личностные особенности, особенности воспитания, религии, профессии…

Мы часто хотим как лучше, в основе наших действий лежит всегда позитивная интенция или намерение. Однако фильтры искажают это намерение, как стекло с фильтрами искажает луч света. И тогда на выходе мы имеем искаженный сигнал, а в нашем случае – деструктор.

Например:

— За упертостью стоит уверенность, твердость.

— За перфекционизмом – желание сделать дело хорошо.

— За обесцениванием – стремление ценить то, что есть.

— За самобичеванием – желание выучить урок, научиться.

— За безразличием – доверие, желание дать больше свободы.

— За отсутствием уважения – легкость, дружелюбие.

— За жалостью к себе – эмпатия и стремление помогать людям.

Намерения хорошие, но все хорошо в балансе.

Что делать с деструкторами?

Прежде всего, осознать, что с деструкторами другого человека ничего не сделать. Попробуйте разобраться хотя бы с одним собственным, чтобы убедиться, насколько это сложно. Да и в принципе, задача каждого – возделывать свой огород, разбираться с собственными тараканами. Если вы осознаете, что ваши начинают мешать другим, а также влияют на вашу эффективность, то работа с деструкторами основывается на следующих принципах:

— Научиться их распознавать. По внешним признакам, по мыслям, словам и нашим действиям, можно осознавать в себе проявления того или иного деструктора. Осознание проблемы – это половина успеха.

— Ругать себя за деструктор бесполезно, даже вредно, ибо это является проявлением самобичевания либо перфекционизма.

— Осознав свои деструкторы, решите, как можно реализовать иначе, сохраняя исходное позитивное намерение, стоящее за деструктором. Проще говоря, как сохранить то ценное, что есть в деструкторе, а его проявление заменить на положительную альтернативу.

Рассмотрим альтернативы для трех популярных форм деструкторов:

— В случае с перфекционизмом: понять, что ошибок не существует. Есть действия, последствия и извлекаемые из них уроки. Научиться извлекать уроки, научиться быть благодарными себе, другим, жизни за эти уроки и действительно учиться на них. Увидеть, насколько мудрой может быть рука жизни, ведущая вас по пути «ошибок», и насколько каждая из них помогает вам развиваться. Научиться относиться легче к себе, к жизни, прощать себя и других, снижать контроль. Например, в случае с микроменеджментом, заранее оговаривать точки контроля, обсуждать их с сотрудниками и следовать им.

— В случае с самобичеванием или обвинениями: понять, что чувство вины бесполезно. И что в каждой жизненной ситуации люди всегда действуют лучшим способом. И если бы вы могли иначе, то действовали бы иначе. Поэтому запомните – никто ни в чем не виноват. Чувство вины – это детское чувство. Там, где есть вина – нет ответственности. А вина и ответственность – это разные вещи. Забудьте про вину, берите на себя ответственность. Это когда вы задаетесь вопросом – какие действия привели к текущему результату, чему меня учит эта ситуация и что мне нужно сделать иначе, чтобы был другой результат? Ответив – действуйте!

— В случае с упертостью: научитесь быть учеником и новичком. В любом деле, сохраняя любопытство, задаваясь вопросом – а что если? Если есть еще идеи, варианты, если я неправ? Помните, что сказал Платон: «Я знаю, что ничего не знаю». Делегируйте, давайте другим свободу действовать, ошибаться, наслаждаясь большей свободой. Направляйте свое внимание в еще неизведанное, неизученное. Проявляйте больше терпимости, развивайте эмпатию и чуткость. Больше слушайте, чем говорите, поощряйте сотрудничество.

Здесь многие подумают – «да, легко сказать!». Действительно, у взрослых людей уже сформировались привычки. И деструкторы – это тоже привычки. Привычки мыслить, говорить, действовать определенным образом. Они формировались годами и не меняются просто по желанию, не меняются ни за день, ни за 21 день.

Принцип тот же как в спортзале: занимайся, практикуй – и будет результат! Нужно время, как минимум 60 дней новых действий из положительных альтернатив, чтобы сформировалась новая привычка. Это долго, однако, если вообще ничего не делать, то результата не будет точно. Как сказал один мудрец: «Даже дорога в 1000 километров начинается с первого шага». Почему бы не начать прямо сегодня?

Кстати, мы завели канал в Telegram, где публикуем самые интересные новости о недвижимости и риэлторских технологиях.

Если вы хотите одним из первых читать эти материалы, то подписывайтесь:

t.me/ners_news.

При перепечатке материалов указание автора и активная ссылка на сайт обязательна!

Настоящий лидер в организации – это человек, за которым люди хотят идти и, к мнению которого, они будут прислушиваться. Помимо этого, лидер должен знать о человеческой натуре, разбираться в человеческой психологии, быть в состоянии направить людей и понизить уровень сомнения о достижении той или иной цели в коллективе. Некоторые люди полагают, что лидерами рождаются и, даже практикуя или учась, невозможно воспитать себе настоящего лидера. На мой взгляд, это мнение ошибочное, потому что каждый человек способен воспитать в себе лидера. Лидер способен повлиять и воодушевить людей к добровольному выполнению определенных задач и целей.

Лидер — это тот, кто осуществляет влияние, причем посредством положительной социальной мотивации. Такая мотивация направлена не на избегание, а на достижение.

Итак, проблема – борьба с деструктивным лидерством и вытекающие отсюда сложности, такие как неравномерное распределение нагрузки, снижение качества работы, увеличение объема работы и отсутствие материальных поощрений.

ЗНАЧИМОСТЬ ЛИДЕРСТВА ДЛЯ РУКОВОДСТВА

Эффективные лидеры уделяют достаточно внимания и задачам, и отношениям и могут исполнять множество различных ролей. В литературе повещённой этому вопросу, можно встретить описание множества стилей лидерства и ролей. Одной из наиболее известных теорий в этой области является теория ролей Роберта Квина, в которой он выделяет восемь ролей лидера: производитель, директор, координатор, контролер, стимулятор, наставник, инноватор и посредник. Изучая дополнительную литературу по психологии управления, мне удалось выделить для себя три основных типа лидерства: эмоциональный лидер, деловой и информационный. Мне хотелось бы остановиться именно на типах лидерства, так как именно данные качества и специфика поведения определяют лидерские особенности и все последующие классификации.

1. Деловое лидерство свойственно для формальных групп, решающих производственные задачи. В его основе такие качества, как высокая компетентность, умение лучше других решать организационные задачи, деловой авторитет, наибольший опыт в данной области деятельности. Деловое лидерство наиболее сильно влияет на руководство. С «деловым» лидером хорошо работается, он может организовать дело, наладить нужные деловые взаимосвязи, обеспечить успех дела.

2. Эмоциональное лидерство возникает в неформальных социальных группах на основе человеческих симпатий — притягательности лидера как участника межличностного общения. Эмоциональный лидер вызывает у людей доверие, излучает доброту, вселяет уверенность, снимает психологическую напряженность, создает атмосферу психологического комфорта. «Эмоциональный» лидер — это человек, к которому каждый человек в группе может обратиться за сочувствием, «поплакаться в жилетку».

3. К «информационному» все обращаются с вопросами, потому что он может объяснить и помочь найти нужную информацию.

Поведение лидера очень индивидуальное и ситуативное, поэтому есть огромное разнообразие путей, по которыми происходит эффективное руководство. Кроме этого, хотелось бы отметить, что харизма и личные качества лидера играют большую роль и являются одной из основных черт проследования, люди идут за сильным и харизматичным лидером. Развитие хороших лидерских навыков занимает время, точно так же, как совершенствование. Без инвестиций времени у немногих людей получится приобрести навыки настоящего лидера.

Значимость лидерства для руководства, его положительное и отрицательное воздействие на управление персоналом придают задаче влияния на этот феномен особую практическую важность. Сама же задача формулируется как управление лидерством, хотя такая формулировка далеко не бесспорна. Итак, является формирование лидерства управляемым или это стихийный в своей основе процесс? Несмотря на отсутствие однозначного ответа на данный вопрос, можно говорить об управлении и о проблеме управления лидерством в организации. В ходе знакомства с модулем и дополнительной литературой я отметила пять основных аспектов:

1. Определение лиц с прирожденными и лидерскими качествами и привлечение таких людей к руководящим позициям. Это направление деятельности может исходить как из тезиса «лидерами рождаются», так и из признания возможности целенаправленного становления лидерами. В первом случае речь идет об обнаружении лидерских способностей и их использовании в организационных целях, во втором — о привлечении в организации уже подготовленных и проявивших себя лидеров.

Известный американский исследователь лидерства Стивен Кови утверждает, что лидеров можно найти на всех уровнях деловой активности, а не только на самом верхнем. Лучшие лидеры обычно придерживаются общего комплекса ценностей, в который входят справедливость, равенство, беспристрастность, целостность, честность, доверие. Каждый человек может определить свою и чужую пригодность к лидерству с помощью следующих восьми критериев[1]:

- Постоянное самосовершенствование;

- положительная энергия, доброжелательность и уклонение от конфликтов,

- вера в других;

- разумное распределение времен;

- оптимизм, свежий взгляд на вещи;

- самокритичность.

2. Развитие лидерства — формирование качеств и навыков. Данный аспект проблемы управления лидерством в организации учитывает возможности формировать и развивать лидерские способности путем обучения и самообучения, мотивирования, тренингов и практического опыта.

3. Интеграция индивидуальных целей и интересов членов команды с организационными целями, реализация потребностей, представительство и защита интересов как отдельных членов группы, так и коллектива в целом. Это устраняет почву для возникновения деструктивных групп и лидеров, деятельность которых наносит ущерб организации, а также повышает авторитет руководителя в глазах сотрудников и значимость делового лидерства по отношению к эмоциональному лидерству.

4. Сочетание разных типов лидерства (формального и неформального) в деятельности руководителя. Подчиненные всегда предпочитают видеть в руководителе не только начальника, но и человека, обладающего лучшими нравственными качествами, заботящегося не только об эффективности организации и о себе лично, но и о сотрудниках.

5. Обеспечение конструктивной направленности лидерской деятельности и устранение деструктивного лидерства. Интеграция лидеров предполагает обеспечение лояльности существующих руководителей, отбор наиболее способных работников, мотивированных на реализацию целей организации, поощрение их профессионально-должностного роста, налаживание хороших отношений и сотрудничества.

АНАЛИЗ МЕТОДОВ И ИНСТРУМЕНТЫ РЕШЕНИЯ

Деструктивный культ (субкультура) — любая авторитарная, иерархическая организация — религиозная, политическая, экстремистская, криминальная, коммерческая, фанатская и пр., которая использует манипулирование и контроль сознания[2].

Деструктивный характер группе придают не ее вера и идеология, а разрушение и деградация личности участников в процессе разнообразного и целенаправленного воздействия.

Признаки деструктивного культа:

1. Харизматическое лидерство. Артистические, ораторские способности и навыки главного «крысолова». В деструктивной группе лидер всегда харизматичен. Он остроумен и энергичен, загадочен, но в то же время прост и обаятелен в общении.Попытка подвергнуть слова и действия главаря обсуждению — крамола, грех, табу, так как иррациональное воздействие можно разрушить только четкими логическими выводами после рационального анализа последствий подобного влияния.Поэтому сомневаться — ненормально. Лидер настолько умен, что не все способны его понять — надо просто верить и подчиняться. Он самый справедливый, так как отстаивает общие интересы, общее дело, престиж группы и каждого ее члена. У такой харизматичной личности часто присутствует не только «комплекс Наполеона».

2. Уверенность членов группы в исключительности признаков своей организации, ее уклада, правил,атрибутов, достижений перед прочими, другими. Манипулирование фактами.

3. Манипулирование сознанием, личным опытом и памятью человека. Скрытая вербовка «клиентов», индивидуальный подход, словесная «анестезия», обман. Реальные цели организации не сообщаются. Каждый завербованный уверен, что в организации он достигнет индивидуальных целей.

4. Эксплуатация и использование участников в корыстных и личных целях.

5. Разделение на «мы» и «они». С «нашими» соблюдается определенный «закон чести», корпоративная этика.

6. Деиндивидуализация членов группы. Человек начинает думать как вся группа, не воспринимает себя отдельно. Самооценка полностью зависит от лидера и группы. Формируется общий застревающий тип мышления с навязчивыми убеждениями, выгодными главному манипулятору. Неприятие любых индивидуальных проявлений личности и взглядов, отличных от общегрупповых.

С моей точки зрения, деструктивные лидеры способны нанести большой ущерб деятельности организации, например лидеры групп сотрудников, которые против нововведений, взяточников и т.д. Для устранения такого рода лидерства существуют различные способы действий. Далее я опишу каждый способ отдельно:

- Административные меры, т.е разрушение системы «лидер — последователи». Могут быть использованы разные средства: увольнение деструктивного лидера или перевод его на другое место работы, изменение его социальной роли за счет перераспределения функций, изоляция лидера, расформирование группы последователей и прежде всего перевод на другие участки работы людей, особенно близких к деструктивному лидеру. Ослаблению влияния такого лидера может так же поспособствовать сокращение коммуникаций между ним и группой, за счет перемещения лидера в другое помещение, загрузки его работой и т.д.

- Индивидуальные беседы, т.е изменение авторитета лидера с пользой для организации. Это может поспособствовать «приближению» не вызывает отрицательной реакции у сотрудников. Однако он эффективен лишь тогда, когда неформальный лидер готов изменить свое отношение и направить свою активность целям организации.

- Переход основополагающих функций деструктивного лидера к руководителю, реализация им управления группой, которое осуществляет или пытается осуществлять лидер. Такого рода лидерство может быть устранено за счет повышения внимания к неформальному общению с людьми, своевременному информированию сотрудников, рассеиванию опасений относительно их будущего и т.д.

- Изменение репутации лидера в глазах его последователей, всего коллектива путем вежливого, но постоянного показа на собраниях низкой профессиональной компетентности лидера, бесперспективности или опасности тех действий, к которым он побуждает, и т.д.

Возьмем международную аутсорсинговую компанию и два абсолютно одинаковых отдела по предоставлению услуг по кадровому администрированию клиентам, назовем их Команда А ( 6 человек) и Команда Б (6 человек), у каждой команды есть непосредственный лидер-менеджер. В Команде А присутствуют два ярко выраженных лидера, которые друг друга дополняют, работа построена слажено. В Команде Б – один лидер, рабочий процесс скрыт от чужих глаз, постоянно закрытая дверь ( в компании присутствует политика открытых дверей), отсутствует обмен опытом и кейсами с коллегами из Команды А, полная изоляция членов группы . Что происходит дальше? В ввиду кризиса начинается череда увольнений, Команда А расформировывается, в том числе увольняются лидеры. Две Команды объединяются в одну, под руководством лидера из Команды Б. В результате, нагрузка членов Команды А увеличилась в два раза, сотрудники Команды Б не изменили своего отношения и, как такого слияния коллектива не произошло. Лидер нынешней команды не корректно распределил задачи между подчиненными и снял с себя ответственность, путем передачи дел сотрудникам из бывшей команды А. Исходя из описанных мной мер борьбы с деструктивным лидерством, рядовой сотрудник не может непосредственно повлиять на такого лидера, но существуют методы борьбы и пути решения.

Специалисты обратили внимание на связь между продолжительностью пребывания у власти и развитием определенных качеств у лидера. Исследование этой зависимости позволило выделить три основных этапа лидерства:

- повышение эффективности;

- постепенное падение эффективности;

- утрата лидером способности к выполнению собственных функций.

Таким образом, существенные причины – увеличение объема работы, в связи с увольнениями и отсутствие мотивации. Исходя их данных причин и обозначенных проблем, вопрос деструктивного лидерства может быть решен путем замены лидера группы или путем перевоспитания (использования инструмента «индивидульные беседы»), чему может поспособствовать высшее руководство компании. К сожалению, маловероятно, что рядовые сотрудники/подчиненные смогут повлиять на процесс управления, но всегда можно обратиться в соответствующие внутренние структурные подразделения с предложением внедрить различные курсы, коллективное обсуждение проблем и совместное принятие решений на уровне локального коллектива. Таким образом, у действующего лидера будет возможность показать себя вне рабочего процесса и продемонстрировать руководству свое отношение и подход и, в свою очередь, у потенциального претендента на лидерство будет такая же возможность. Также, одним из способов борьбы с деструктивным лидерством может быть организация еженедельных собраний, на которых важной частью будет постановка целей для каждого сотрудника. Предложение объединить всех сотрудников в одно помещение будет также эффективным, таким образом можно будет определить нагрузку и внести предложения по взаимодействию и поддержке.

Чтобы удержать клиентов, необходимо повысить качество предоставляемых услуг, что может быть достигнуто путем общения менеджера/лидера с представителями клиентских компаний и составление, своего рода листа опроса. Данный процесс может быть проконтролирован со стороны ответственного сотрудника путем неформального диалога с лидером о рабочем процессе с определенной компанией.

Зачастую, труд сотрудников недооценивается, но такой факт, как кризис должен не разрушать коллектив, а объединять. Лидеру необходимо как можно чаще обращаться к сотрудникам с посвящением в текущую ситуация в компании. Путем совместных усилий можно сформировывать план на месяц или год методами, описанными в курсе лекций Тайм-менеджмента. Важный момент, с случае конкретной компанией необходима совместная работа, совместная постановка целей, путем использования критерий SMART.

Следующий важный аспект, вытекающий из всего перечисленного — это мотивация (вся совокупность стойких мотивов, побуждений, определяющих содержание, направленность и характер деятельности личности, ее поведения). Отсутствие мотивации к работе и достижению общих целей порождает деструктивный менеджмент. Известно, что для того, чтобы осуществлялась деятельность, необходима достаточная мотивация. Однако, если мотивация отсутствует, увеличивается уровень напряжения, вследствие чего в деятельности (и в поведении) наступают определённые разлады, т. е. эффективность работы ухудшается. Экспериментально установлено, что существует определённый оптимум (оптимальный уровень) мотивации, при котором деятельность выполняется лучше всего (для данного человека, в конкретной ситуации). Последующее увеличение мотивации приведёт не к улучшению, а к ухудшению эффективности деятельности. На мой взгляд, в данной ситуации Контроль руководства будет хорошим средством повышения мотивации как сотрудников, так и менеджера.

Подводя итоги, мне хотелось бы отметить, что профессиональное долголетие лидера и продолжительность каждого из этапов его лидерства зависят от многих социально-психологических факторов, необходимо постоянно самосовершенствоваться, развивать собственную компетентность, и самокритичность, развивать командный дух в организации.

Помимо личных нравственных качеств, которые лидеру необходимо развивать самостоятельно, непосредственному руководству следует уделять огромное внимание не только бизнесу организации, но и локальным управленцам, так как можно упустить момент, как эффективный лидер станет деструктивным. И, тем не менее, для любого лидера наступает время, когда надо освободить место для нового лидера, в котором нуждается организация. Для самого лидера и организации будет лучше, если это произойдет вовремя.

Источник

«

Первый способ – разрушение образовавшейся системы «лидер – последователи», используя административные меры. Это может быть увольнение лидера, перевод его на другую должность, изменение его социальной роли через изменения в организационной структуре.

Можно расформировать последователей, подальше распределив тех, кто больше всех сблизился с деструктивным лидером. При этом можно еще загрузить таких людей работой, затрудняющей неформальное общение.

Однако все это крайние, «хирургические», способы. Иногда они оправданы, все-таки на весах судьба компании, хотя настолько запущенные случаи бывают крайне редко.

Проблема в том, что такие резкие меры не будут поддержаны окружающими, поскольку будут восприняты как несправедливость, а это может запустить еще один деструктивный процесс.

Лучше использовать другой способ устранения деструктивного лидерства – применение способностей деструктивного лидера для пользы компании. Достичь подобного можно путем индивидуальных бесед, назначения его на руководящую должность, проявление к нему особого внимания. У сотрудников это не вызывает протеста. Однако такой вариант возможен, если лидер способен, готов и настроен менять свою активность в конструктивную сторону.

Есть еще способ – перехват формальным лидером функций деструктивного лидера. К примеру, если неформальный лидер информирует о том, что происходит, потому что формальному некогда, – нужно, чтобы формальный начал сообщать команде официальные новости компании. Неформальное лидерство обычно возникает из-за пустоты – там, где формальный лидер недорабатывал.

Есть еще способ – подрыв репутации деструктивного неформального лидера. Компрометация – неприятный шаг, но это может спасти ситуацию. Для вывода деструктивного лидера на чистую воду желательно применять честные методы, позволяющие открыть суть деструктивного поведения и при этом не вызвать негатива в коллективе.

Не стоит использовать нечистые приемы, отравляющие компанию.

Лучший способ исправить ситуацию требует креатива от «команды спасения». Самый желательный способ – это предложить коллективу что-то другое и позитивное, более сильное, чем влияние деструктивного лидера. Это может быть марафон, соревнование, интересный проект, тимбилдинг или обучающая программа, о которой все мечтали.

Introduction

The media frequently reports stories about so-called “bad bosses.” On a closer look, these destructive leader behaviors come in many forms. Recently, Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon, was announced as winner of the world’s “worst boss” award at the 3rd International Trade Union Confederation World Congress in Berlin, because Amazon is said to exploit its workers. Microsoft was also in the press, when a senior manager was arrested on federal charges for stealing more than 9 million USD from the company to pay for a lavish lifestyle. Steve Jobs of Apple, on the other hand, was known for an aggressive leadership style, shouting at and humiliating others (Isaacson, 2011).

It is intuitively compelling that an abusive leader, who shouts, has a different effect on a follower than a leader who exploits followers, or a leader who violates organizational rules. Unfortunately, we do not have empirical evidence to know if this is simply a lay assumption or if followers do have different reactions to different types of destructive leader behaviors. One reason for this is that comparative research in the field of destructive leadership is scarce. Rather, empirical work in the field is characterized by isolated investigations of separate destructive leadership constructs, resulting in a body of evidence that seems somewhat scattered and disconnected. This is unfortunate for both theory and practice. From a theoretical perspective, we still know too little about the unique and relative contributions of different destructive leader behaviors regarding negative follower outcomes. As a consequence, practitioners have little guidance when it comes to distinguishing, detecting, and managing different forms of destructive leadership in organizational contexts.

This is further aggravated since a broad body of research evidence suggests that negative information has a stronger influence on us and that we perceive and process negative events in a more nuanced way than positive ones (Baumeister et al., 2001; Unkelbach et al., 2008). This “bad is stronger than good” phenomenon has important implications for the domain of leadership. Not only are destructive leader behaviors likely to have a far stronger impact on followers than constructive behaviors, but the adverse impact of such destructive behaviors is likely to outweigh the benefits gained from positive relationships (e.g., with coworkers or customers). Negative interactions with a leader are likely perceived as more nuanced and more dissimilar from each other than in the case of positive information about the leader (Unkelbach et al., 2008). In our view, this makes understanding the differential effects of different destructive leader behaviors even more urgent. Thus, our main purpose in this article is to investigate whether and to what degree different types of destructive leadership may affect followers in a distinct way. In our theoretical model, we draw on the work of Einarsen et al. (2007) and Schyns and Schilling (2013). We argue that the target of the leader behavior and the level of hostility are key factors in understanding the potentially unique effects of different types of destructive leader behavior on followers. Specifically, we focus in our study on three constructs of destructive leadership: (1) abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), as a behavior high on hostility focusing on the follower; (2) exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2017), as a behavior low on hostility focusing on the follower; and (3) organization-directed destructive leadership (Thoroughgood et al., 2012), as a behavior low on hostility focusing on the organization.

In order to answer the question of how far these different destructive leader behaviors elicit different reactions in followers, we draw on emotions as the first reaction to an interaction with a leader (Dasborough, 2006). Furthermore, we investigate the intention to leave, one of the most well-researched outcomes in destructive leadership research (Schyns and Schilling, 2013) and highly relevant to organizations. We thus deem these outcomes as most suited to understanding different follower reactions to destructive leadership.

Theoretical Background

Leadership is one of the most important relationships in the workplace and the way leaders give direction, assign tasks, and handle conflict has a strong influence on followers (Yukl, 2012). With this, it becomes particularly important to consider what social research refers to as “negativity bias.” In a seminal article famously titled “Bad is Stronger than Good,” Baumeister et al. (2001) cite extensive evidence showing that bad events and interactions “have more impact than good ones, and bad information is processed more thoroughly than good” (p. 323). To account for this phenomenon, Baumeister et al. (2001) draw on evolutionary selection: in order to survive threats, it was important for organisms to recognize and remember negative information more strongly than positive. As a consequence, negative information has greater emotional and motivational significance. This has important implications for the study of destructive leadership, since destructive leaders should therefore have a strong influence on followers’ emotional state and their motivation to act.

Related to this, more recent research indicates that there is a significant difference between how we generally process positive versus negative information. Unkelbach et al. (2008) describe this in the density hypothesis. They argue that information is generally perceived as more similar to other positive information compared to negative information’s similarity to other negative information (i.e., negative information is perceived as more dissimilar to other negative information). Thus, while destructive leadership generally impacts followers more strongly, followers may also be very sensitive to the unique features of different destructive leader behaviors.

Against this backdrop, a great deal of attention has been given to the nature and processes of destructive leadership over the last 15 years (for a review, see Schyns and Schilling, 2013). Different definitions and constructs of destructive leadership exist, all describing different behaviors. The most widely researched construct is abusive supervision (Schyns and Schilling, 2013). This refers to repeated hostile and aggressive yet nonphysical behaviors toward followers (Tepper, 2000). One of the most recent constructs describes a more prevalent form: exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2017) refers to genuinely self-interested leader behaviors, such as using followers for personal gain and taking credit for followers’ work. Other researchers have pointed to destructive leader behaviors such as accepting bribes, stealing, or making personal use of company property (Einarsen et al., 2007; Thoroughgood et al., 2012).

In short, the literature on destructive leadership describes a multitude of different constructs (for a review, see Schyns and Schilling, 2013). At the same time, efforts have been made to integrate and organize these different approaches (Einarsen et al., 2007; Thoroughgood et al., 2012; Krasikova et al., 2013; Schyns and Schilling, 2013). In the present work, we follow the seminal taxonomy provided by Einarsen et al. (2007), who describe destructive leadership behavior along two dimensions: destructive leader behaviors targeting the followers versus destructive behaviors that target the organization. This distinction is well established and commonly used when it comes to organizing empirical evidence on destructive leadership (Aasland et al., 2010; Thoroughgood et al., 2012; Schyns and Schilling, 2013). In addition, we follow the work of Schyns and Schilling (2013), who concluded that the core of destructive leadership lies in the hostile or hindering nature of the leader’s behavior. They defined destructive leadership as “a process in which over a longer period of time the activities, experiences and/or relationships of an individual or the members of a group are repeatedly influenced by their supervisor in a way that is perceived as hostile and/or obstructive” (2013, p. 141).

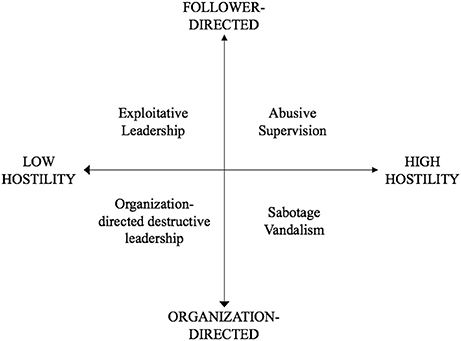

Taken together, these two aspects (i.e., the target of behavior and the level of hostility) offer a useful basis for differentiating constructs. Cross-tabulation of the two dimensions results in four theoretical destructive leadership behavior categories, as shown in Figure 1. The underlying rationale for these categories is presented below.

Figure 1. Destructive leadership types. The mentioned constructs are not exhaustive but reflect the most typical construct for each category.

Follower-Directed Behaviors High in Hostility

Constructs describing follower-directed destructive leader behaviors usually stem from the bullying literature (Tepper, 2000) and refer to genuinely abusive forms of leadership, high in hostility. The most widely researched construct appears to be abusive supervision (Schyns and Schilling, 2013). Abusive supervision refers to “subordinates’ perceptions of the extent to which their supervisors engage in the sustained display of hostile verbal and nonverbal behaviors, excluding physical contact” (Tepper, 2000, p. 178). Other variants of this notion are, for instance, petty tyranny (Ashforth, 1994), social undermining (Duffy et al., 2002), strategic bullying (Ferris et al., 2007), or despotic leadership (De Hoogh and Den Hartog, 2008). While none of these constructs conceptualizes follower-directed destructive leadership in exactly the same way, they all have in common that they describe leaders who behave in a hostile and aggressive (yet nonphysical) manner toward followers. This includes repeatedly intimidating and belittling followers. However, the most established assessment of these constructs is abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000).

Follower-Directed Behaviors Low in Hostility

Recently, Schmid et al. (2017) have introduced the concept of exploitative leadership to describe a prevalent leadership behavior that targets the followers but is not inherently hostile or aggressive. Exploitative leadership describes behaviors “with the primary intention to further the leader’s self-interest by exploiting others, reflected in five dimensions: genuine egoistic behaviors, taking credit, exerting pressure, undermining development, and manipulating” (Schmid et al., 2017, p. 26). Self-interested behaviors, such as taking credit for followers’ work or undermining the development of followers to benefit the leader, are low in regard to hostility. Schmid et al. (2017) posited that exploitative leadership may even be overtly friendly toward followers. Certainly, we can imagine situations where the self-interested behaviors of a leader may even benefit the organization. If a leader’s goals and the organization’s goals align, the leader may push followers to achieve higher targets. This may be done in a seemingly friendly way, and not by being directly abusive.

Organization-Directed Behaviors Low in Hostility

Thoroughgood et al. (2012) described organization-directed destructive leadership around behaviors that violate the established rules and social norms of conduct in an organization. There is a broad variety of behaviors that fall under this category—for instance, theft (e.g., stealing small materials such as pens, but also money or time), talking negatively about the organization, using company properties for personal gain, as well as fraud or corruption, and even substance abuse at work (Thoroughgood et al., 2012). While these behaviors certainly vary in terms of their seriousness and harmfulness for the organization, they are not high on hostility as such.

Organization-Directed Behaviors High in Hostility

Behaviors that fall under the category of organization-directed leadership characterized by high levels of hostility have not been explicitly described in the destructive leadership literature. However, from a theoretical viewpoint and borrowing from research in the field of workplace deviance (Martinko et al., 2002), such behaviors refer to acts of genuine aggressiveness toward the organization. Examples would be sabotage, equipment destruction, or vandalism (e.g., spreading computer viruses). We assume that this type of destructive leadership represents a low base rate phenomenon. While this is in part true for all forms of destructive leadership, such explicitly hostile behaviors against the organization are likely to be performed particularly covertly and thus remain unseen by others. As such, they are less likely to elicit effects on followers. Thus, in the current study, we focus on those behaviors that are more prevalent and feasible to assess and that are established constructs in the destructive leadership literature.

In conclusion, we propose that two important differentiating factors of destructive leadership are: (1) the level of hostility and (2) the target of the behavior. Based on this, in the next section we develop different hypotheses for three recurring destructive leadership behaviors: abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, and organization-directed destructive leadership.

Different Effects of Different Destructive Leadership Behaviors

In this part of our article, we delineate the proposed different effects of different destructive leadership behaviors on relevant follower outcomes.

When assuming that the target of the leader’s behaviors and the level of hostility are the differentiating factors between different types of destructive behavior, these two factors would naturally impact how an employee reacts. As mentioned before, negative information, such as destructive behavior of a leader, has higher emotional and motivational significance than positive information (Baumeister et al., 2001). Thus, we first assume that followers’ emotions, as the most proximal reaction (Sy et al., 2005; Bono and Ilies, 2006; Bono et al., 2007) when confronted with destructive leadership, are likely to differ as a function of different destructive leadership behaviors.

Secondly, we follow the argument by Baumeister et al. (2001) that negative information has a strong motivational significance, in that it triggers an action (e.g., avoiding a negative stimulus). Thus, when relating this to destructive leadership, different levels of hostility are likely to have a different impact on the motivation to leave a leader. We thus propose to focus on emotions and the intention to leave the leader (i.e., turnover intention) in analyzing the different effects of abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, and organization-directed destructive leadership.

A very proximal effect a leader’s behaviors have is on their followers’ emotions (Sy et al., 2005; Bono and Ilies, 2006; see, for example, Bono et al., 2007). As such, all experiences of destructive leadership are likely paralleled by negative emotions. However, the extent of the negative affect is thought to vary, depending on the level of hostility and if the follower is targeted directly. Several scholars (e.g., Schaubhut et al., 2004; Tepper, 2007; Thau and Mitchell, 2010) have argued that destructive leadership is destructive since it is a threat to the self-worth of the followers. Abusive supervision is described as rather high on hostility. By targeting the follower—for instance, by ridiculing followers in front of others or even telling them they are incompetent—abusive supervisors would very directly harm the self-worth of followers (Burton and Hoobler, 2006). Accordingly, hostile and aggressive behaviors, such as described in abusive supervision, have been consistently related to negative affect in empirical studies (Aquino et al., 1999; Tepper, 2007). In line with this, we posit that abusive supervision has a strong impact on employees’ negative affect.

Exploitative leaders, on the other hand, will take credit for work or manipulate followers to further their own self-interest. Such behaviors, while still targeting the follower directly, are lower on hostility and should thus have a less detrimental effect on followers’ self-worth. While being exploited would certainly relate to negative affect, we posit that it does so less strongly than abusive supervision. On the other hand, leaders that show anti-organizational behaviors (Thoroughgood et al., 2012) will show negative behaviors that are not a direct attack on the followers’ self-worth. Stealing from the organization, or talking negatively about it, primarily targets the organization, and is rather distal from the follower. We posit that this should have the least strong effect on followers’ negative affect.

Thus, we specify the following predictions:

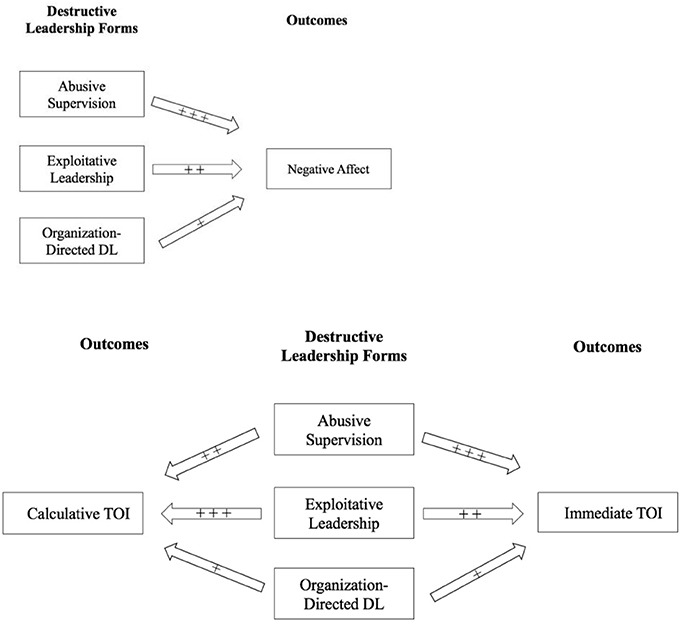

Hypothesis 1: All three destructive leader behaviors (i.e., abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors) will have a positive relationship with follower negative affect.

Hypothesis 1a: Abusive supervision will have a stronger positive relationship with followers’ negative affect in comparison to exploitive leadership and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors.

Hypothesis 1b: Exploitative leadership will have a stronger positive relationship with followers’ negative affect in comparison to organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors.

Tepper et al. (2009) argued that when followers are confronted with self-worth threatening interactions, they feel a need to empower themselves. A very strong way to empower themselves is turnover, since a follower who intends to leave the job is less dependent on their supervisor (Tepper et al., 2009). We expect exploitative leadership, just like abusive supervision and organization-directed destructive leadership, to relate to general turnover intentions, as previous research has shown (Tepper, 2000; Schyns and Schilling, 2013; Schmid et al., 2017). We therefore predict that all three leadership styles will cause followers to reconsider their employment options. However, the degree of self-worth threat is assumed to vary depending on the level of hostility and how directly a follower is targeted by the behavior. We thus expect that the urgency of the turnover intentions will vary. Since abusive supervision represents a more direct attack on the follower with high levels of hostility, this should relate to followers considering immediate turnover (i.e., leaving the situation immediately). We argue that exploitative leadership, as a less hostile behavior, poses less of a self-worth threat to followers, resulting in a less immediate need to leave the situation. Therefore, followers under exploitative leadership will take a rather more calculative approach and consider staying until, for example, the next career level is reached. Since organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors are more distal and do not target the follower directly, the effect is more difficult to predict. It may be that a leader harming the organization confronts followers with behaviors that run against their feeling of what is right and wrong. On the other hand, the anti-organizational behavior of the leader may be too distant; as Thoroughgood et al. (2012, p. 18) put it “…such behaviors might not increase turnover intentions as quickly as overtly abusive acts.” Therefore, we only specify hypotheses for abusive supervision and exploitative leadership.

Hypothesis 2: All three destructive leadership behaviors (i.e., abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, organization directed destructive leadership) will have a positive relationship with general turnover intentions.

Hypothesis 2a: Exploitative leadership will have a stronger positive relationship with followers’ calculative turnover intentions in comparison to abusive supervision and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors.

Hypothesis 2b: Abusive supervision will have a stronger positive relationship with followers’ immediate turnover intentions in comparison to exploitative leadership and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors.

Our research model is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Research model. + + + indicates the strongest hypothesized effect; DL, destructive leadership; TOI, turnover intentions.

Methods

To test the hypotheses under investigation, we conducted two studies with different designs. In Study 1, we used a working sample and adopted a scenario-based approach to manipulate destructive leadership (i.e., abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, organization-directed destructive leadership). Then, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions and provided self-reports on affective reactions and turnover intentions. Study 2 was a field study in which employees from various occupations and organizations rated their immediate supervisor in terms of destructive leadership (i.e., abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, organization-directed destructive leadership). In line with Study 1, self-reports of affective reactions and turnover intentions were collected.

We certify that the research presented in this manuscript has been conducted within the ethical standards of the DGP (German Psychological Society) regarding research with human participants and scientific integrity. We adhere to the ethical standards of the DGP, since in Germany there is no legal regulation for approval of research through a research ethics committee for the social sciences, but ethics questions are addressed within a framework by professional associations.

Study 1

Sample and Procedures

Building on prior research on leadership that has successfully used the vignette method (e.g., De Cremer, 2006; Van Dierendonck et al., 2014), we created three hypothetical scenarios for abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors by covering the core elements of each construct (see Appendix).

Participants for this study were recruited via an open online survey conducted within the network of three Master’s students. On the first page of the online survey, participants were informed that participation was voluntary and by continuing to the second page, they consented to participating in the study. A prerequisite for participating in the survey was that participants were employed full time. In total, 297 participants took part in the online survey and were randomly assigned to one of the three experimental groups (92 in the exploitative leadership, 113 in the abusive supervision, and 92 in the organization-directed destructive leadership condition). In total, 136 respondents were female, the mean age was 25.64 (SD = 7.04), and the majority of the participants (95.6 percent) worked in the for-profit sector.

Measures

Manipulation check

After presenting respondents with the scenarios, they were asked to rate them in terms of abusive supervision, exploitative leadership, and organization-directed destructive leader behaviors to test whether the manipulation of the independent variable was successful. Exploitative leadership was assessed by six items taken from the exploitative leadership scale (α = 0.87) introduced by Schmid et al. (2017). These six items covered the five dimensions of exploitative leadership (i.e., egoism, taking credit, exerting pressure, undermining development, manipulating). An example item was “This leader prioritizes their own goals over the goals and needs of followers.” Abusive supervision was measured by six items taken from the abusive supervision scale by Tepper (2000; α = 0.89). An example item was “This leader puts me down in front of others.” Organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors were captured with seven items from the anti-organizational leader behavior sub-scale developed by Thoroughgood et al. (2012; α = 0.92); a sample item was “This leader violates company policy/rules.” All leadership items were rated on a five-point scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Emotional reactions

Emotional reactions Emotional reactions were measured by using the German version (Krohne et al., 1996) of the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988). The PANAS contains two ten-item sub-scales to measure both negative and positive affect. In the current study, both sub-scales showed sufficient reliability (α = 0.75 for both sub-scales). Respondents were instructed to indicate the extent to which they felt this way (e.g., active, interested, or excited for positive affect versus distressed, upset, or guilty for negative affect) toward the leader described in the scenario. Responses were given on a five-point scale (ranging from 1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely).

Turnover intentions

We assessed three indicators related to turnover intention. Firstly, we adapted two items from Kirchmeyer and Bullin (1997) to assess general turnover intentions (“I would start looking for a new job”) as well as immediate turnover intentions (“I would hand in my notice immediately”). Moreover, we developed an item to measure calculative turnover intentions (“I would wait for the next career step is reached before leaving”). Responses were anchored on a five-point continuum (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree).

Results

Manipulation check

The manipulation check was tested by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), including post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test. The results revealed a significant effect of leadership style manipulation on the perception of exploitative leadership [F(2, 235) = 7.41, p < 0.001]. Post-hoc comparisons indicated that the exploitative leadership manipulation was indeed perceived as being more exploitative (M = 4.32; SD = 0.76) compared to abusive supervision (M = 3.94; SD = 0.80) and organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors (M = 3.87; SD = 0.75). Similarly, there was a significant effect of leadership manipulation on the perception of abusive supervision [F(2, 237) = 109.33, p < 0.001]. Post-hoc analysis indicated that the abusive supervision vignette was indeed perceived as being more abusive (M = 4.44; SD = 0.64) than the exploitative leadership condition (M = 3.02; SD = 0.83) and the organization-directed destructive leadership condition (M = 3.00; SD = 0.75). Finally, we found a significant effect of leadership manipulation on the perception of organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors [F (2, 238) = 109.66, p < 0.001]. Post-hoc analysis showed that the organization-directed destructive leadership behaviors condition was indeed perceived as being more organization-directed destructive (M = 4.10; SD = 0.78) than the abusive supervision condition (M = 2.37; SD = 0.80) and the exploitative leadership condition (M = 2.40; SD = 0.84). Taken together, this pattern shows that the leadership manipulations were successful.

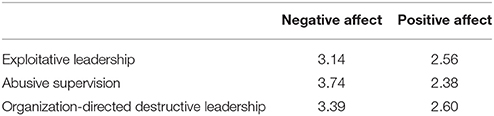

Hypothesis tests concerning followers’ emotional reactions

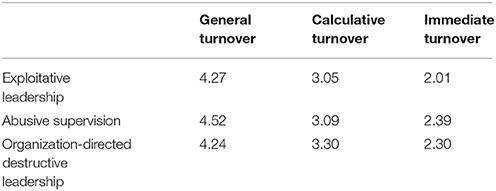

Next, we tested our hypotheses regarding the proposed different effects of the three destructive leader behaviors. The first set of hypotheses refers to affective reactions. Although the focus of our analysis was the effects of destructive leader behavior on negative affect, we deemed it useful to account, too, for the effect on positive affect. The mean scores pertaining to the three conditions are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean scores of emotional reactions (Study1).

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) with destructive leadership as independent variable and negative and positive affect as dependent variables showed a significant multivariate effect [F(4, 504) = 7.20, p < 0.001; Wilk’s Λ = .89, η2 = 0.05]. Yet, univariate testing found the effect to be significant only for negative affect [F(2, 253) = 13.28, p < 0.001], and no significant effect was found for positive affect [F(2, 253) = 2.92, p = 0.06]. Post-hoc comparisons using the Tukey HSD test indicated that negative affect was significantly higher in the abusive supervision condition (M = 3.60, SD = 0.66), as compared to the exploitative leadership condition (M = 3.11, SD = 0.54) and the organization-directed destructive leadership condition (M = 3.34, SD = 0.62). No difference between the exploitative leadership and the organization-directed destructive leadership conditions was revealed. Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported.

Next, we adopted an explorative perspective and examined whether the different types of destructive leadership under investigation would be related to specific facets of negative affect. Specifically, building on the work of Mehrabian (1997), Janke and Glöckner-Rist (2014) found evidence that the negative affect items of the PANAS reflect two sub-dimensions, upset and afraid. The upset dimension contains the upset, hostile, and irritable items, whereas the afraid dimension includes the guilty, ashamed, afraid, nervous, jittery, distressed, and scared items. Using the Pleasure-Arousal-Dominance (PAD) emotion model (Mehrabian, 1996) as a framework, Mehrabian (1997) found that the upset dimension is characterized by high levels of displeasure (i.e., genuine negative emotional state) and, though less heavily, by arousal (i.e., mental and/or physical activity level). In contrast, the afraid dimension relates less strongly to displeasure, more to arousal, and also more to submissiveness (i.e., lack of control over others or situations).

The mean scores for the two sub-dimensions that we obtained in the current study are shown in Table 2. Again, a MANOVA with destructive leadership as the independent variable and the upset and afraid dimensions as dependent variables revealed a significant multivariate effect [F(4, 504) = 15.08, p < 0.001; Wilk’s Λ = 0.80, η2 = 0.11].

Table 2. Mean scores of negative affect sub-dimensions (Study1).

Separate one-way ANOVAs for each dimension showed the following pattern. For the upset dimension, we found a significant effect of the leadership manipulation [F(2, 252) = 10.62, p < 0.001]. Post-hoc analyses revealed no significant difference between the exploitative leadership condition (M = 4.16, SD = 0.79) and the abusive supervision condition (M = 4. 25, SD = 0.72). Yet, both conditions were significantly different from the organization-directed destructive leadership condition (M = 3.73, SD = 0.81). Next, also for the afraid dimension, we found a significant main effect [F(2, 253) = 17.20, p < 0.001]. Respondents scored similarly high in the abusive supervision (M = 3. 32, SD = 0.85) and the organization-directed destructive leadership conditions (M = 3.18, SD = 0.69), which were both significantly different from the exploitative leadership condition (M = 2. 67, SD = 0.63).

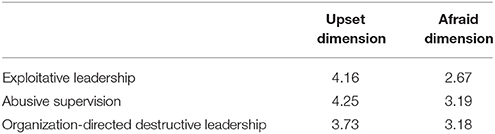

Hypothesis tests concerning followers’ turnover intentions

The MANOVA we conducted showed a statistically significant difference in turnover intentions based on the leadership manipulation [F(6, 482) = 2.69, p < 0.05, Wilk’s Λ = 0.93, η2 = 0.03]. Separate ANOVAs showed the following pattern. For general turnover, we found a significant effect of the leadership manipulation [F(2, 243) = 3.70, p < 0.05]. Post-hoc analysis using the Tukey HSD procedure revealed a significant difference between the abusive supervision (M = 4.52, SD = 0.68) and the organization-directed destructive leadership conditions (M = 4.24, SD = 0.84). For the other combinations, no significant differences were revealed. Overall, general turnover intentions were substantially high in all three conditions, thus confirming hypothesis 2. Next, for calculative turnover intentions, we found no significant effect of the leadership manipulation [F(2, 243) = 1.24, p = 0.32]. Therefore, hypothesis 2a was not confirmed. Finally, immediate turnover significantly differed between the conditions [F(2, 243) = 3.58, p < 0.05]. Post-hoc analyses showed that immediate turnover was lower in the exploitative leadership (M = 2.01, SD = 0.90) than in the abusive supervision (M = 2.39, SD = 0.92) condition, thus confirming hypothesis 2b. The organization-directed destructive leadership condition (M = 2.30, SD = 0.96) did not significantly differ from the other two groups.

Brief Discussion

This study revealed a series of distinct effects, in particular for exploitative leadership and abusive supervision. As predicted, abusive supervision emerges as the strongest precursor to overall negative affect.

Both abusive supervision and exploitative leadership are associated with stronger feelings of displeasure (i.e., upset) compared to organization-directed destructive behaviors. Yet, with regard to the afraid dimension of the PANAS, an interesting difference was revealed, with lower scores for exploitative leadership relative to the abusive supervision condition. This suggests that abusive supervision is more strongly related to anxiety among followers, reflected in increased arousal and feelings of submissiveness (Mehrabian, 1997). With regard to turnover, all three forms of negative leadership were related to high general turnover intention. While the level of calculative turnover intention was inconspicuous among the three conditions, abusive supervision tends to relate to higher immediate turnover reactions.

Overall, the results were only partly as expected. This may be because of the hypothetical nature of the scenarios. Therefore, in Study 2 we designed a field study to test the same hypotheses.

Study 2

Sample and Procedures

We gathered valid responses from 167 employees from various organizations in Germany who rated their immediate leaders in terms of destructive leadership and provided self-reports on emotional reactions and turnover intentions. Respondents were contacted via snowball sampling, starting with the authors’ professional network. The majority of the participants (72 percent) worked in the for-profit sector (28 percent worked in non-profit organizations or in the public sector). The mean age was 36.22 years (SD = 12.13) and 63.30 percent of the respondents were male. On average, the respondents had been working for their current supervisor for 4.89 years (SD = 5.48) and organizational tenure was 7.98 years on average (SD = 8.69). In terms of education, 67 percent of the respondents held a university degree.

Measures

Destructive leadership measures

Exploitative leadership was assessed with the full 15-item exploitative leadership scale developed by Schmid et al. (2017). Abusive supervision was measured according to the full 15-item abusive supervision scale by Tepper (2000). Organization-directed destructive leader behaviors were captured with the measure developed by Thoroughgood et al. (2012). Sample items can be seen in the description of measures in Study 1. Respondents rated the frequency of destructive leader behaviors on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“frequently if not always”).

Outcome measures

For the outcomes (i.e., emotions and turnover), we used the same items with the same response format as in Study 1.

Results

Validity of measures

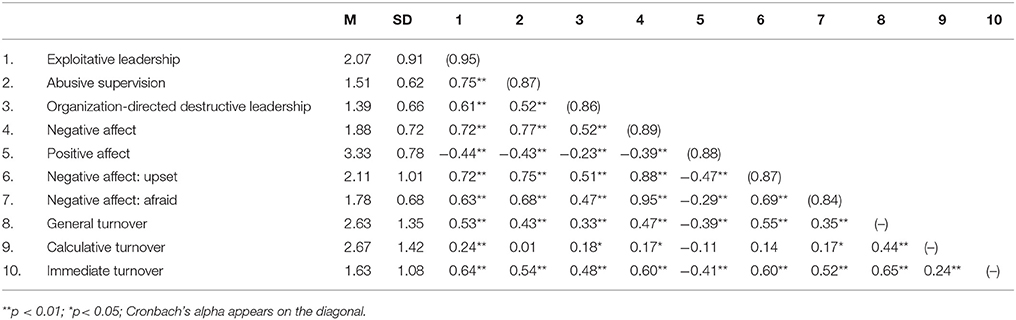

Table 3 reports the descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables.

Table 3. Mean scores of turnover intentions (Study 1).

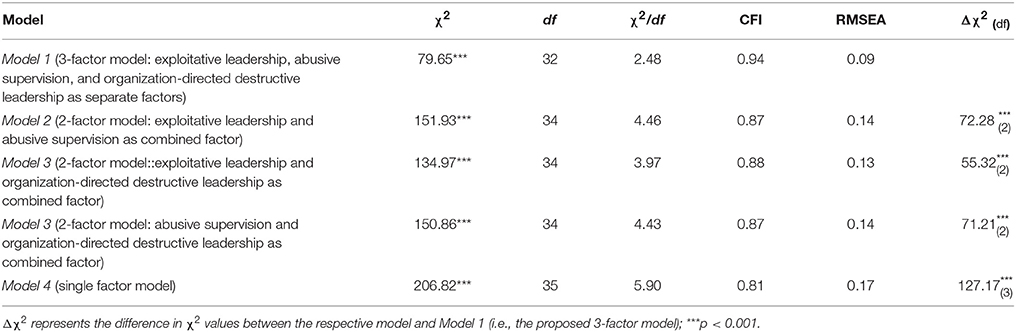

Prior to testing the hypotheses under investigation, we examined whether the measures we used represented valid tools to assess our target constructs. To this end, we used confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) in AMOS and tested the factorial integrity of our measures. In a first step, we conducted CFA on the item level for each measure separately (i.e., exploitative leadership, abusive supervision, organization-directed destructive leadership) and examined the factor loadings and item reliabilities. While all items of the exploitative leadership measure had excellent psychometric properties, we dropped several items of the other two measures (i.e., abusive supervision, organization-directed destructive leadership) because they did not represent the underlying construct well (i.e., factor loadings were below 0.60 and item reliabilities below 0.40; Hair et al., 2006).

Next, we tested the discriminant validity of our measures. Because of the relatively large number of estimated parameters in the overall model and the small sample size, we created item parcels for all latent leadership constructs (Landis et al., 2000). For exploitative leadership, we formed five parcels based on the five dimensions specified by Schmid et al. (2017) (i.e., egoism, taking credit, exerting pressure, undermining development, and manipulation). For abusive supervision and organization-directed destructive leadership, we used the factorial algorithm to create parcels (see Matsunaga, 2008). By sequentially including the items with the highest to the lowest factor loadings, while alternating the direction of item selection, three parcels were formed for abusive supervision and two parcels for organization-directed destructive leadership.

On this basis, we tested a series of theoretically viable factor models. Table 4 shows that a three-factor model with the three target constructs as latent variables and parcels as indicators obtained the best model fit and was preferable over alternative solutions. These results provide evidence that our measures captured distinct constructs versus common source effects.

Table 4. Measurement models (Study 2).

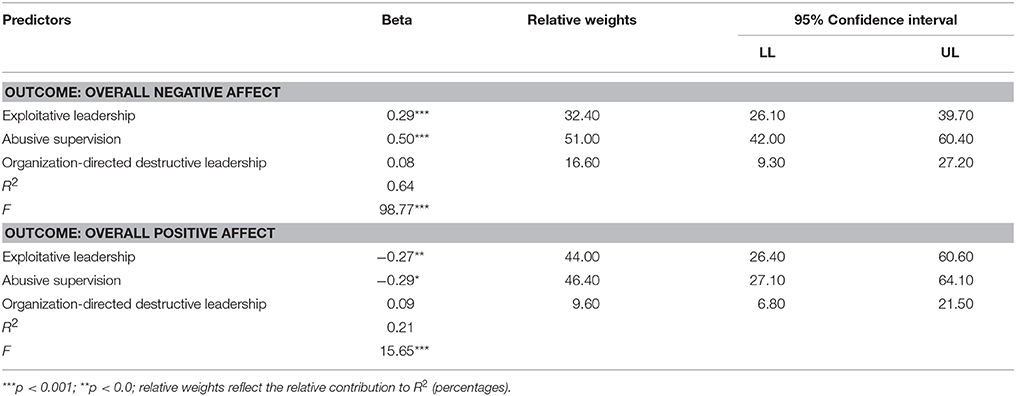

Hypothesis tests concerning followers’ emotional reactions

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses. In addition, given the high correlations among the destructive leadership measures, we followed the procedures suggested by Lorenzo-Seva et al. (2010) and applied relative weight analysis. The results of these procedures are depicted in Tables 5, 6.

Table 5. Descriptive statistics and correlations (Study 2).

Table 6. Effects of destructive leadership on overall negative and positive affect (Study 2).

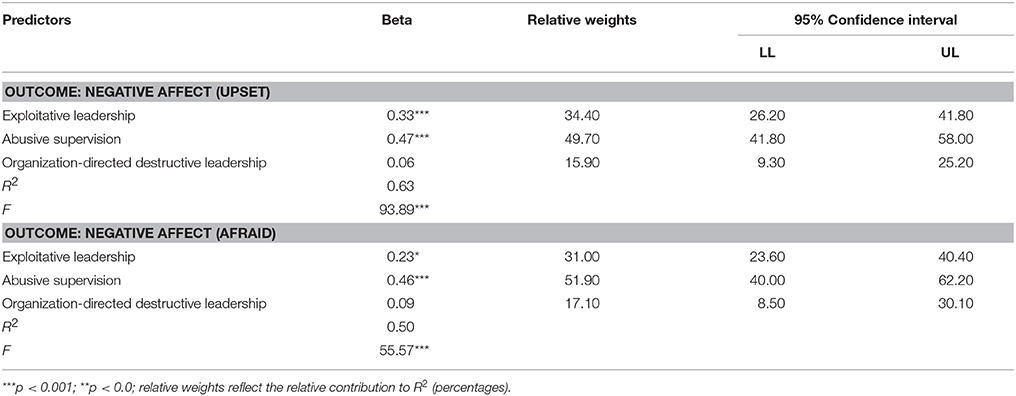

Abusive supervision was the strongest predictor of overall negative affect (β = 0.50, p < 0.001), followed by exploitative leadership (β = 0.29, p < 0.001), and organization-directed destructive leadership (β = 0.08, ns). Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported. For overall positive affect, abusive supervision (β = −0.27, p < 0.01) and exploitative leadership (β = −0.29, p < 0.05) exerted a similar negative effect, while the effect for organization-directed destructive leadership was not significant (β = 0.09, ns). With regard to the sub-dimensions of negative affect (see Table 7), the following pattern was revealed: the upset dimension was best predicted by abusive supervision (β = 0.47, p < 0.001), followed by exploitative leadership (β = 0.33, p < 0.001). The effect for organization-directed destructive leadership was not significant (β = 0.06, ns). In a similar vein, abusive supervision was the strongest predictor for the afraid dimension (β = 0.46, p < 0.001) followed by exploitative leadership (β = 0.23, p < 0.05). Again, organization-directed destructive leadership had no predictive value here (β = 0.09, ns).

Table 7. Effects of destructive leadership on negative affect sub-dimensions (Study 2).

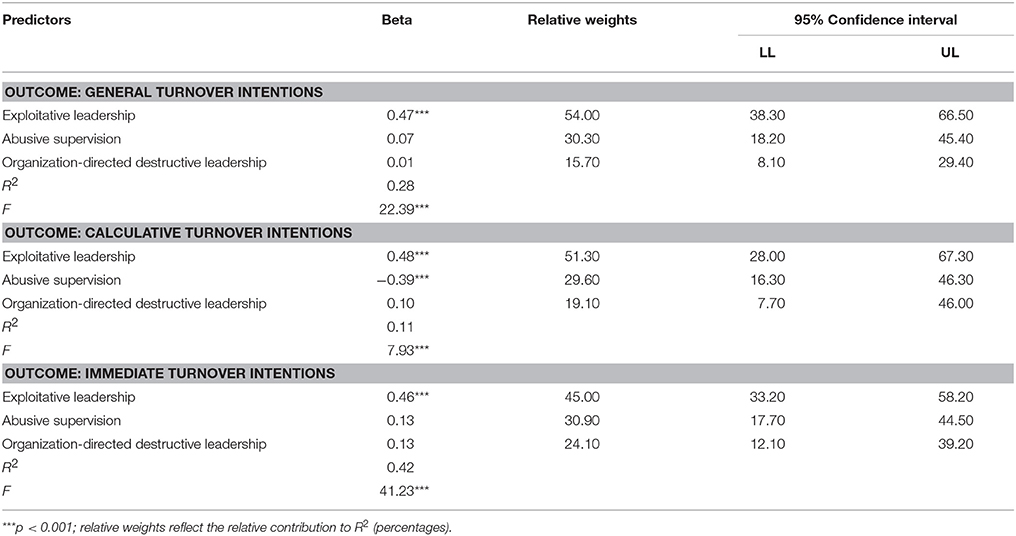

The next set of hypotheses refers to different types of turnover intention. For general turnover intention, the results of regression analysis revealed only exploitative leadership as a significant predictor (β = 0.47, p < 0.001). Relative weight analysis, however, showed that the other two leadership forms also explained variance in general turnover intention (see Table 8); however, exploitative leadership clearly exerted the strongest effect. While these results do not fully confirm hypothesis 2, relative weights analysis does point to an effect in the expected direction.

Table 8. Effects of destructive leadership on turnover intentions (Study 2).

With regard to calculative turnover, we found a positive effect for exploitative leadership (β = 0.48, p < 0.001), whereas the effect of abusive supervision was negative (β = −0.39, p < 0.001). Given that the two predictor variables were highly correlated (r = 0.75, p < 0.001), while abusive supervision did not correlate with the outcome variable (r = 0.01, ns), this pattern shows the classic signs of a suppression effect (Tzelgov and Henik, 1991). This means that abusive supervision shares no or only little variance directly with the outcome variable but contributes to the regression equation by removing irrelevant variance from the other predictor variables. This is also reflected in the results of relative weight analysis, showing that exploitative leadership explained the major portion of variance in calculative turnover intentions (see Table 6). While hypothesis 2a is again not fully confirmed, taken together, this pattern points to what was predicted.

Interestingly, for immediate turnover, only exploitative leadership was a significant predictor in the regression analysis (β = 0.46, p < 0.001). Again, relative weight analysis revealed that the other two leadership forms also explained variance in immediate turnover intention, yet only to a moderate extent (see Table 6). Thus, hypothesis 2b was not supported.

Brief Discussion

In line with the results found in Study 1, both abusive supervision and exploitative leadership were found to have a negative relationship with positive affect. With regard to negative affect, however, different patterns were found. Abusive supervision was related most strongly to overall negative affect and to the afraid sub-dimension of negative affect. Also, it was more strongly related to the upset sub-dimension, relative to exploitative leader behavior. This is different from what we found in Study 1, where exploitative leadership had an equally strong effect on the upset sub-dimension. Overall, the pattern found in Study 2 supports the notion that abusive supervision is both generally and relative to exploitative leadership more strongly related to negative emotional reactions of followers. Organization-directed destructive leader behavior seems to play a marginal role when it comes to followers’ emotional reactions. A potential explanation for this could be that followers perceive such leader behaviors as rather distal—i.e., as actions they can more efficiently distance themselves from.

For turnover intentions, the results are more complex. While all three types of destructive leadership behavior relate to general turnover intention, when examining the relative weights, exploitative leadership has the strongest relationship. However, exploitative leadership had the strongest positive relationship with calculative turnover intention—i.e., followers would stay until the next milestone in their career was reached before leaving—whereas abusive supervision had limited impact. This is in line with our hypothesis: because of the stronger self-worth threat, followers would be less likely to have a calculative approach.

However, when looking at immediate turnover intention, a low effect was found for abusive supervision. Whereas this may seem counterintuitive at first, the underlying explanation may be that the decision to leave a job depends on many factors that are situational, and may depend on the individual follower’s personality.

General Discussion

The main purpose of this article was to investigate if different destructive leadership behaviors may affect followers in a distinct way. Our focus was on three destructive leadership constructs: abusive supervision (Tepper, 2000), exploitative leadership (Schmid et al., 2017), and organization-directed destructive leadership (Thoroughgood et al., 2012). To answer the question of how far these behaviors would elicit different reactions in followers, we investigated followers’ emotions as the first reaction to an interaction with leaders (Dasborough, 2006) and the intention to leave. The results of both a scenario-based experimental study and a field study suggest that exploitative leadership does indeed influence different outcomes compared to leaders behaving in an abusive manner or leaders behaving in a manner that harms the organization. As expected, all three constructs had a positive relationship with negative affect. Yet, with regard to the afraid dimension of the PANAS, higher scores for abusive supervision were found. Organization-directed destructive leader behavior showed marginal relevance with regard to different urgencies of turnover intention. However, exploitative leadership and abusive supervision affected calculative and immediate turnover intentions to a similar degree. In what follows, we discuss the theoretical and practical implications of these results in more detail.

Theoretical Implications